Afghanistan’s leaders have often been concerned about the intentions of foreigners wanting to build railways into their country – and not without reason.

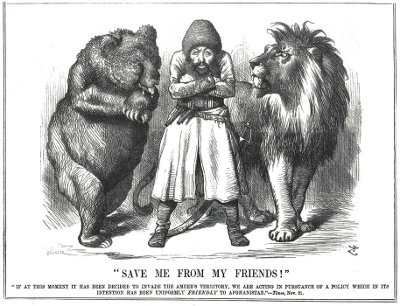

The Amir of Afghanistan sandwiched between the British lion and the Russian bear. Punch, 30 November 1878. Source: Middle East Cartoon History

Throughout the nineteenth century the British political and military authorities were worried that Russia might advance through Afghanistan towards India, threatening British rule in the subcontinent. Even if a full-scale Russian invasion and occupation of India was unlikely, any move towards India would tie-up British resources dealing with both the Russians themselves and also any Indian uprising which they might inspire. Britain saw defence of India’s North West Frontier, now part of Pakistan, as essential to the ‘Great Game’ of politics played across Central Asia by the two rivals.

In 1857 William Andrew, Chairman of the Scinde, Punjab & Delhi Railway, suggested that railways to the Bolan and Khyber passes would have a strategic role in responding to any Russian threat.1 No action was taken until 1876, when Britain decided to keep at least one route into Afghanistan open all year round to permit the rapid deployment of troops from Karachi to counter any threat to India. Orders were given that a railway should be built to Quetta, near the Afghan border, and this developed into a scheme to reach Kandahar.

The Second Afghan War (1878-80) broke out between Britain and Afghanistan before work on the railway could begin. The war gave a new urgency to the need for easier access to the frontier, and on 18 September 1879 the Viceroy’s council decided to make do with a line through the Bolan pass usable only in fair weather. Work began just three days later, and after four months the first 215 km of the line was complete, opening from Ruk to Sibi in January 1880. On 27 March 1880 the Morning Post commented “after three and twenty years of apathy the necessity has been realised and now these railways are being constructed.” The railway was built to the 1 676 mm Indian broad gauge.

Beyond Sibi the terrain was more difficult. Reconnaissance parties had reached Kandahar by December 1879, but Afghanistan was enemy country, making it difficult to find an optimal route for the line. It was realised it would not be possible to for the railway to reach Quetta before the conclusion of the war, and so the railway was given a lower priority. When a new cabinet under Gladstone was formed in April 1880 the planned Kandahar extension was put to one side.

In March 1880 Britain and Persia agreed the Herat Convention. Persia would take control of the Afghan city of Herat subject to certain conditions, including permitting British soldiers

to be stationed there. Article seven of the draft agreement stated that

If a railway or telegraph be constructed to Kandahar the Shah [of Persia] at the request of the Queen [Victoria] would facilitate its extension to Herat in all ways in his power and would contribute thereto from the surplus of the Herat revenues according to his ability.

At first the Persian foreign minister requested the removal of this article. He eventually agreed to its inclusion, but objected to the conditions regarding the assessment of the revenue of the city.2

In 1880 Russia began to build the Trans-Caspian railway.3 In Britain there was concern that Russia might seize Herat, and extend their new railway to the city.

In response to this threat Britain restarted work on the railway to Afghanistan. To avoid alerting Russia to this work it was described as the “Harrai road improvement project”, and camels were used for construction traffic instead of the more usual temporary railway lines. This deception was abandoned when Russia occupied the city of Mary in 1883, and the line was developed as the Sind Peshin State Railway. Over 320 km long, the line reached Quetta in March 1887, through barren mountains inhabited by armed tribesmen.

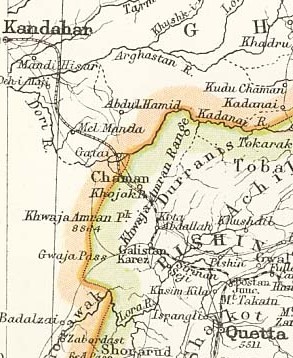

On 30 September 1891 the Chaman Extension Railway was opened, linking Bostan, north of Quetta, to the Afghan frontier. The buffer stop lay 5 km beyond Chaman fort, and just 200 m short of the Durand line, the Afghanistan-India border which was drawn around the railway when the frontier was fixed by Sir Mortimer Durand in 1893.

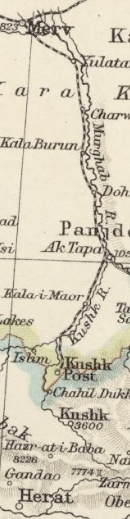

A supply depot was set up at Chaman containing the rails, sleepers and bridge parts required to extend the line the remaining 108 km to Kandahar in the event of a military emergency. Meanwhile, across Afghanistan, the Russians stockpiled materials at Kushka4 to allow the rapid construction of a line to Herat.

Amir Abdul Rehman, ruler of Afghanistan between 1880 and 1901, banned railways and the telegraph from entering Afghanistan, in case they were used in any British or Russian invasion. Rehman commented “there will be a railway in Afghanistan when the Afghans are able to make it themselves” and said “as long as Afghanistan has not arms enough to fight against any great attacking power, it would be folly to allow railways to be laid throughout the country.” Rehman forbade his subjects from travelling on the British line to Chaman,5 the construction of which he described as “just like pushing a knife into my vitals”.6 The Afghan army produced a manual on how to destroy railway tracks in the event of an invasion threat.7

In 1891 Captain AC Yates wrote a booklet setting out arguments in favour of building a railway to Seistan, rather than Kandahar, to allow the defence of Herat against Russia.8 “The press and the public are at this moment advocating the extension of our railways to Kandahar; but that this could be done without precipitating a rupture of our relations with the Amir is doubtful”.

Around 1910 there was discussion9 regarding extending the Chaman line to Kandahar, and beyond to Herat and the Russian railhead at Kushka. In the event, the line was never extended across the border. It did however carry traffic from Afghanistan, with a daily ice-packed train bringing fresh fruit grown in Afghanistan to the cities of India until the 1940s.

A through railway link from Europe to India had long been contemplated, but the schemes raised concerns for the security of the subcontinent. In 1910 a Russian syndicate proposed a Trans-Persia railway, running from Tehran to Yezd, Kerman, Seistan and Nushki. This raised the risk of Russian troops being able to occupy Kandahar and Quetta, outnumbering available Indian army forces.

In 1911 a British study looked at the implications of Russian railway construction in the light of the successful movement of troop on the Trans-Siberian line during Russia’s war with Japan (1904-1905).10 The Trans-Persia line faced political problems “in that it would cause alarm and suspicion in Afghanistan, as its rails lead direct to the Afghan Frontier, which may give rise to tribal excitements that may prove beyond the Amir’s power to control. The measures taken to restore confidence may involve us in complications with other European Powers.”

The study’s author commented “No connection between this line and either Afghanistan or Northern Baluchistan should be permitted”,

Russian railways now stretched from Orenburg to Tashkent and Samarkand. “The further extension can only be accomplished in peace, or with the consent of the Amir, which is hardly likely to be given; or during a war with Afghanistan. The bridging of the Oxus [Amu-Darya] is estimated to take four months to complete”. It was estimated that after reaching the Amu-Darya it would take the Russians 16 months to extend the railhead to Doshi. The report also considered that an extension of the Trans-Caspian railway from Kushka into Afghan territory would only be possible with consent or in war time. Rails were stacked at Kushka, and it was estimated that the line could be laid to the Helmud in 18 months.

“The extension of Russian or Persian railways through Afghanistan should be more strongly resisted than ever” said the report. The author speculated that the German-backed Baghdad railway could be extended to the Afghan frontier, but handwritten annotations on the Public Record Office’s copy of the booklet suggest officials thought this somewhat unlikely.

The author concluded that “The present attitude of the Amir concerning them [i.e. railways] may change rapidly, as it has recently with regard to roads in Afghanistan. Thus the construction of these two lines [Trans-Caspian from Kushka, an extension from Samarkand] is probably only a matter of time.”

Next page: Merv to Kushka railway

References

- Couplings to the Khyber PSA Berridge 1968 ↩

- England & Afghanistan Dilip Kumar Ghose 1960 ↩

- Railways At War John Westwood 1980 ↩

- Kuskha is now Serhetabat in Turkmenistan, and was also known as Gusgy in Turkmen. ↩

- Reform and Rebellion in Afghanistan 1919 – 29 Leon B Poullada ↩

- The Life of Abdur Rahman, Amir of Afghanistan, volume 2, page 159 ↩

- Afghan rail plan among proposals for donors, CNN News report, from Reuters 2002-01-21 ↩

- The Transcaspian Railway and the Power of the Russians to Occupy Herat Captain AC Yate 1891-04-29 PRO WO 106 178 ↩

- Baluchistan to Russia railway map http://users.ev1.net/~jtslrr/1910h46.jpg ↩

- Afghanistan: Military aspect of Railway communication between Europe and India – Russian aspirations towards Afghan-Turkestan 1911, PRO WO 106/58 ↩

Hello,

I find your website about Afghanistan informative.

I hope you’ll continue to keep it up to date and just as informative & as interesting.

Thank you.

I found some minor mistakes in the text. You have missed an important strategic point regarding proposed rail track from Russia to Kabul via Bamian. It was considered the shortest rout. Russian sources says it is possible to lay the track within four months.

I’m always keen to receive more details and corrections. In particular, I have made very little use of Russian sources – not least because I don’t speak Russian.