A new page about the three steam locomotives at the National Museum of Afghanistan.

History

Construction of the Trans-Caspian railway

A page from The Graphic of 22 September 188x (looks like a 3, but the caption says 8), showing the construction of the Trans-Caspian Railway in what is now Turkmenistan.

Turkmenistan railways

“Turkmenistan” magazine had an issue about the country’s railways (PDF) in March 2006, which you can read online in English and Russian.

Turkmenistan is a bit of an information black hole, beyond the legendary revolving gold statue of the late president. There doesn’t even seem to be a website for the national railway company (unless anyone knows better?).

It appears that since 2004 Chinese suppliers have replaced most of the Soviet-era fleet with a range of single and double-unit diesels. I’m attempting to put together a list of the different types they have, but am finding the supplier and official news agency’s numbers don’t add up – if you can help, please do get in touch!

Amanullah-Wagen trains mentioned by German President

The President of Germany, Christian Wulff, mentioned the Berlin U-Bahn’s Amanullah-Wagen trains during a speech in Kabul on 16 October 2011.

Deutsche und Afghanen hat es schon immer zueinander gezogen. Bereits in der ersten Hälfte des vergangenen Jahrhunderts arbeiteten deutsche Ingenieure in Afghanistan, lernten Afghanen an der Amani-Schule in Kabul Deutsch. Der Besuch von König Amanullah 1928 in Berlin wurde von den Deutschen mit großer Begeisterung aufgenommen. Noch heute nennen die Berliner den U-Bahn-Zug, mit dem er damals durch Berlin fuhr „Amanullah“. Er war bis 1989 in Betrieb und Sie können das letzte Exemplar bei Ihrem nächsten Besuch in Berlin im Museum bewundern. Und in einigen Jahren wird vielleicht der Zeitpunkt kommen, gemeinsam einen neuen Zug zu benennen.Source:Mittagessen auf Einladung von Präsident Karsai anlässlich des Staatsbesuchs in Afghanistan, Kabul, 16 October 2011

Chappar Rift railway

Images of the remains of the Chappar Rift railway in Pakistan, in a video by Aurang Zaib Khan

There is a history of the line at All Things Pakistan

New book on Financing India’s Imperial Railways

A book to be published in September 2011 looks potentially very interesting: Financing India’s Imperial Railways, 1875–1914, by Stuart Sweeney.

The Indian railway network began as a liberal experiment to promote trade and commerce, the distribution of food and military mobility. Sweeney’s study focuses on Britain’s largest overseas investment project during the nineteenth century, offering a new perspective on the Anglo-Indian experience.

Chapter 3 is entitled “Military Railways in India, 1875–1914: Russophobia, Technology and the Indian Taxpayer”. The book’s index is available at publisher Pickering & Chatto’s website, and there are a number of mentions of Afghanistan, the Kandahar Railway and related matters.

By the looks of it, this will be a serious academic study. Unfortunately, and probably not unrelated to this, it will also be sixty quid…

(other forthcoming books from the publisher include “The Unpublished Letters of Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke”. Will the very existence of such a book trigger some kind of publishing grandfather paradox?)

The Frontier Clasp and its Railways

…the British Indian government had just started making inroads to the Khyber Agency by extending it’s railway beyond Jamrud.

The Peshawar – Jamrud railway had already been constructed on which the “Flying Afridi” train service would make a trip once a day. This train service, part of the greater Kabul River Railway or the Loye Shilman railway project, was to be extended much deeper into the Khyber Agency. The initial survey by Captain Macdonald was to follow the upstream right banks of the River Kabul along the Loye Shilman territory till the village of Palosi on the Afghan border. Although less challenging, this route was scrapped due to political issues of the time with the then Amir of Afghanistan, Amir Habibullah Khan and also probably due to the sheer number of bends in the River along the route.

Source: The Frontier Clasp and its Railways, Omar Usman, Khyber.org, 2011-03-14

There is a map which shows the Kabul River railway.

Articulated steam locomotives planned for Kandahar

With Azerbaijan being in the news this weekend, it might be a good time1 to mention the book The Transcaucasian Railway and the Royal Engineers by RAS Hennessey (Trackside Publications, 2004. There is a review of it at The International Steam Pages).

On page 26 the book mentions the use of class Ѳ (an obsolete Russian letter, fita), Bryansk-built 0-6-6-0 Mallet articulated compound steam locomotives on the Transcaucasian Railway.

“An interesting speculation about these Mallets is that their basic design had in mind imperial Russian dreams of a line from Merv to Kandahar, Afghanistan, and thence to Quetta, then in British India (now in Pakistan). The tough conditions of the TCR’s Armenian lines provided a good testing ground for possible locomotives to work this line.”

The reference says this information comes from J Nurminen and FM Page’s book Russian Locomotives vol 2 1836-1904 (I think this should read 1905-24, as 1836-1904 is volume 1, by A De Pater and FM Page). I haven’t yet found a library with a copy of the book to look up the reference.

According to Hennessey, the TCR locomotives “were costly to acquire and their complexity resulted in slow, expensive servicing and maintenance […] Two were apparently spotted derelict in the 1930s at Kars, by then in Turkey.”

There are no photographs of a fita class locomotive in the book. However this photo I spotted on display at the St Petersburg railway museum in March 2011 shows one:

The Russian-language Wikipedia has some basic information on the Ѳ class, though with no mention of Afghanistan. There is also a public domain image from the Kirov plant’s archive showing one with detail differences to the machine in the St Petersburg museum photo:

- Tenuous link to popular culture or what? And anyway, I thought the Moldovan gnomes should’ve won. ↩

“The most irresistible of all civilizers”

The movements of Russia and England in the East continue to keep pace with each other, and whatever may be the result of the pending dispute, the gain to civilization will be unquestionably great.

The projected Afghan railway is a report from the New York Times of 26 October 1879 about plans for a railway to Kandahar from Shikarpore, in what was then British-ruled India but is now Pakistan.

They don’t write ’em like that any more….

The Russian march on India

Poverty Bay Herald, Volume XXVIII, Issue 9118, 11 April 1901, Page 4 at the National Library of New Zealand. The author is presumably Sir Henry Norman, 1st Baronet.

THE RUSSIAN MARCH ON INDIA.

A SECRET RAILWAY LINE.

(By Henry Norman, M.P., in Scribener’s Magazine.)

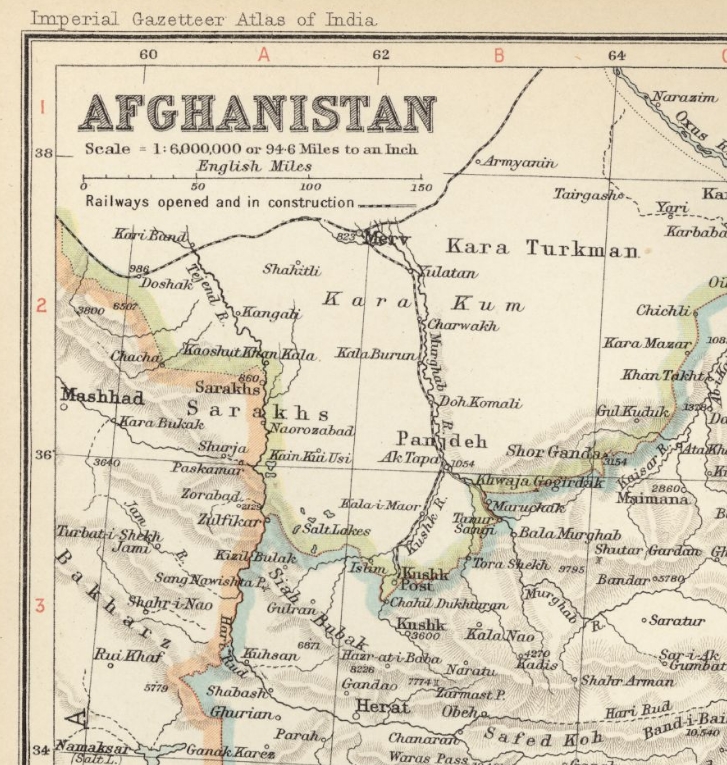

Merv – once the “Queen of the World,” and a household word in England, thanks to O’Donovan and Marvin and Vambery, as the possible cause of war with Russia, whose absorption of Central Asia brought her here m 1884— just a year before Parliament, at Gladstone’s behest, voted £11,000,000 of war money at a sitting in view of Rusia’s next step south. Now the whole oasis of Merv, one of the most fertile spots m the whole world, is as Russian as Riga, and when you say “Merv” in Central Asia you mean a long, low, neat stone railway station, lit by a score of bright lamps in a row, where the train changes engines, where in a busy telegraph office a dozen operators sit before their clicking instruments; and if you are a Russian officer or official you mean also a bran new town where a pestilent malarial fever is sure to catch you sooner or later, and very likely to kill you. But Merv has long ceased to be a Russian boundary, for m the dark you can see a branch line of railway stealing southward across the plain. This is the famous Murghab branch, the strategical line of one hundred and ninety miles along the river to the place the Russians call Kushkinski Post, on the very frontier of Afghanistan, a short distance from Kushk itself, and only eighty miles from Herat. The Russians keep this line absolutely secret, no permission to travel by it having been ever granted to a foreigner. My own permission for Central Asia read, “With the exception of the Murghab branch.” A foreigner once went by train to Kushk Post, however, but this was an accident and it is another story.

This line is purely strategic and military. Neither trade nor agriculture is served by it; nor would anybody ever buy a ticket by it, if it were open to all the world. Moreover, it runs through such a fever-haunted district that Russian carpenters, who can earn two roubles a day, throw up the job and go back to earn fifty kopecks at home. The line is simply a deliberate railway menace to Great Britain. It serves, and can ever serve, only the purpose of facilitating the invasion of India, or of enabling Russia to squeeze England by pretending to prepare the first steps of an invasion of India, whenever such a pretence may facilitate her diplomacy in Europe. This fact should always be borne in mind. Nothing would embarass Russia more than to “have her bluff called,” in poker language — to be compelled to make her threat goood. But it may safely be prophesied that many a time we shall hear of troops going from the Caucasus to the Afghan frontier, as she did for an “experiment” last December, and when this happens England must look, not at Afghanistan, but to China or Persia or the Balkans. Some day — and perhaps before long — she will collect a mixed force there without England’s knowledge, and seize Herat by a coup de main, m the confident belief that the British Government will do once more That it has so often done before, namely, accept tamely the accomplished fact. In simple truth, Herat is at her mercy. And the cat does not look at the cream for ever. The Merv-Kushk line, I may add, is now completed, and two regular trains a week run over it, at the rate of something less than ten miles an hour, reaching the Afghan frontier terminus in eighteen hours. But I do not fancy that Kushk Post itself has anything very wonderful to show yet in the way of military strength. It is interesting, however, as one stands here on the edge of the platform and looks down the few hundred yards of this mysterious line visible in the dark, to reflect that if the future brings war between England and Russia its roaring tide will flow over these very rails for the invasion of India, and that if it brings peace this will be a station on the through line between Calais and Kandahar. Some day, surely, though it may be long, long hence, and only when tens of thousands of Russian and British soldier-ghosts are wandering through the shades of Walhalla, the traveller from London will hear on this very platform the cry, “Change here for Calcutta !”

Imperial Gazetteer of India map of Afghanistan from 1909 showing the Russia railway from Merv (Mary) to Kushka (Serhetabat). (Source: Digital South Asia Library)