Poverty Bay Herald, Volume XXVIII, Issue 9118, 11 April 1901, Page 4 at the National Library of New Zealand. The author is presumably Sir Henry Norman, 1st Baronet.

THE RUSSIAN MARCH ON INDIA.

A SECRET RAILWAY LINE.

(By Henry Norman, M.P., in Scribener’s Magazine.)

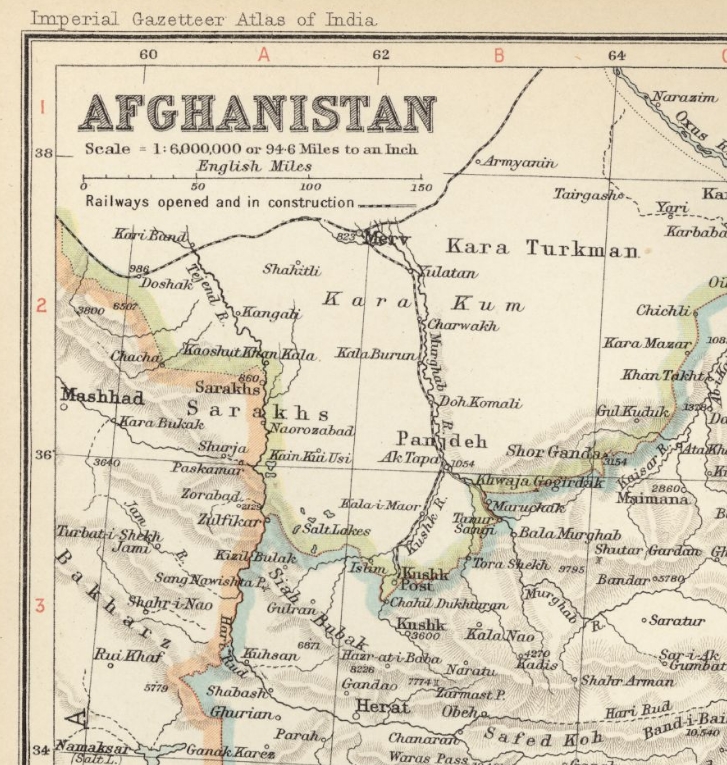

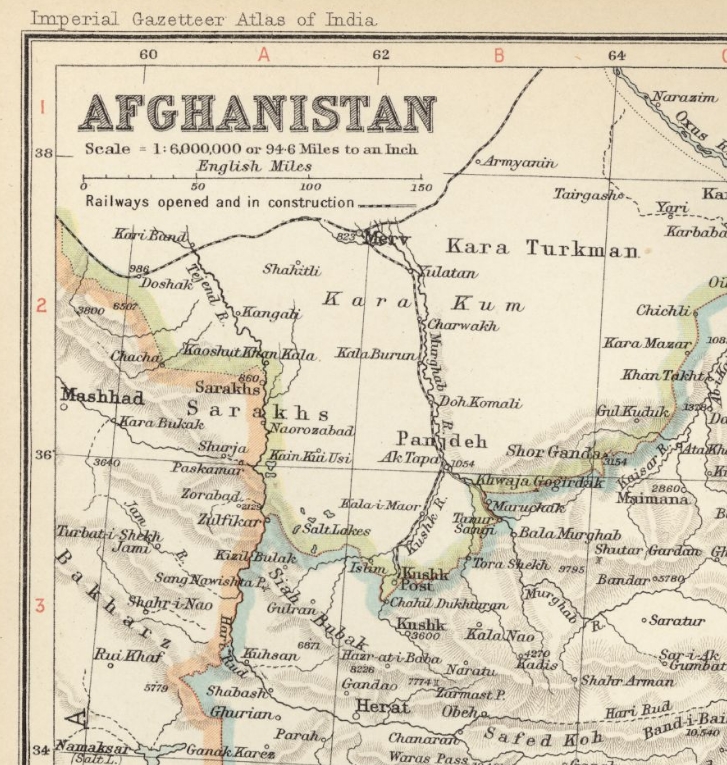

Merv – once the “Queen of the World,” and a household word in England, thanks to O’Donovan and Marvin and Vambery, as the possible cause of war with Russia, whose absorption of Central Asia brought her here m 1884— just a year before Parliament, at Gladstone’s behest, voted £11,000,000 of war money at a sitting in view of Rusia’s next step south. Now the whole oasis of Merv, one of the most fertile spots m the whole world, is as Russian as Riga, and when you say “Merv” in Central Asia you mean a long, low, neat stone railway station, lit by a score of bright lamps in a row, where the train changes engines, where in a busy telegraph office a dozen operators sit before their clicking instruments; and if you are a Russian officer or official you mean also a bran new town where a pestilent malarial fever is sure to catch you sooner or later, and very likely to kill you. But Merv has long ceased to be a Russian boundary, for m the dark you can see a branch line of railway stealing southward across the plain. This is the famous Murghab branch, the strategical line of one hundred and ninety miles along the river to the place the Russians call Kushkinski Post, on the very frontier of Afghanistan, a short distance from Kushk itself, and only eighty miles from Herat. The Russians keep this line absolutely secret, no permission to travel by it having been ever granted to a foreigner. My own permission for Central Asia read, “With the exception of the Murghab branch.” A foreigner once went by train to Kushk Post, however, but this was an accident and it is another story.

This line is purely strategic and military. Neither trade nor agriculture is served by it; nor would anybody ever buy a ticket by it, if it were open to all the world. Moreover, it runs through such a fever-haunted district that Russian carpenters, who can earn two roubles a day, throw up the job and go back to earn fifty kopecks at home. The line is simply a deliberate railway menace to Great Britain. It serves, and can ever serve, only the purpose of facilitating the invasion of India, or of enabling Russia to squeeze England by pretending to prepare the first steps of an invasion of India, whenever such a pretence may facilitate her diplomacy in Europe. This fact should always be borne in mind. Nothing would embarass Russia more than to “have her bluff called,” in poker language — to be compelled to make her threat goood. But it may safely be prophesied that many a time we shall hear of troops going from the Caucasus to the Afghan frontier, as she did for an “experiment” last December, and when this happens England must look, not at Afghanistan, but to China or Persia or the Balkans. Some day — and perhaps before long — she will collect a mixed force there without England’s knowledge, and seize Herat by a coup de main, m the confident belief that the British Government will do once more That it has so often done before, namely, accept tamely the accomplished fact. In simple truth, Herat is at her mercy. And the cat does not look at the cream for ever. The Merv-Kushk line, I may add, is now completed, and two regular trains a week run over it, at the rate of something less than ten miles an hour, reaching the Afghan frontier terminus in eighteen hours. But I do not fancy that Kushk Post itself has anything very wonderful to show yet in the way of military strength. It is interesting, however, as one stands here on the edge of the platform and looks down the few hundred yards of this mysterious line visible in the dark, to reflect that if the future brings war between England and Russia its roaring tide will flow over these very rails for the invasion of India, and that if it brings peace this will be a station on the through line between Calais and Kandahar. Some day, surely, though it may be long, long hence, and only when tens of thousands of Russian and British soldier-ghosts are wandering through the shades of Walhalla, the traveller from London will hear on this very platform the cry, “Change here for Calcutta !”

Imperial Gazetteer of India map of Afghanistan from 1909 showing the Russia railway from Merv (Mary) to Kushka (Serhetabat). (Source: Digital South Asia Library)