Photos of steam locos at the museum, taken by Stefan Schmitt on 6 February 2010. “Evidence of attempts of Amanullah Shah’s attempts to ‘modernize’ Afghanistan in the 1920’s. In those days they even had 7kms of railway in Kabul! The locomotive in the foreground and the Darulaman Palace he built.”

steam loco

King Amanullah’s 1920’s Train

Amanullah sought German companies and engineers into the country to build roads, bridges, dams and royal palace in Darulaman, a suburb of Kabul. The locomtives were transported by ship to Mumbai and then pulled by elephant in passes through the Hindu Kush, where a couple of hundred metres of rail were laid. After 20+ years of civil war turmoil and the destruction of Kabul, they’re overgrown by thistles and thorn bushes are three rusty steam engines and the carriage labelled “Made in Germany”

Flickr photo by Tanya Murphy (username “turnip!”, © All Rights Reserved), taken on 2 November 2009.

Kabul loco from a different angle

“This was the first steam train of the Kabul Railroad – we got chased away from taking pictures”. Photo taken by Timothy Bates, 12 November 2010

View from the museum

The view from the Archaeology Museum. In the foreground are early trains, a form of transportation first brought to Afghanistan by the British. Unfortunately there is no train service in Afghanistan today.

Flickr photo taken on 14 January 2009 by Lauras Eye (CC BY-ND 2.0). The locos were supplied from Germany.

Outside the Kabul Museum

Articulated steam locomotives planned for Kandahar

With Azerbaijan being in the news this weekend, it might be a good time1 to mention the book The Transcaucasian Railway and the Royal Engineers by RAS Hennessey (Trackside Publications, 2004. There is a review of it at The International Steam Pages).

On page 26 the book mentions the use of class Ѳ (an obsolete Russian letter, fita), Bryansk-built 0-6-6-0 Mallet articulated compound steam locomotives on the Transcaucasian Railway.

“An interesting speculation about these Mallets is that their basic design had in mind imperial Russian dreams of a line from Merv to Kandahar, Afghanistan, and thence to Quetta, then in British India (now in Pakistan). The tough conditions of the TCR’s Armenian lines provided a good testing ground for possible locomotives to work this line.”

The reference says this information comes from J Nurminen and FM Page’s book Russian Locomotives vol 2 1836-1904 (I think this should read 1905-24, as 1836-1904 is volume 1, by A De Pater and FM Page). I haven’t yet found a library with a copy of the book to look up the reference.

According to Hennessey, the TCR locomotives “were costly to acquire and their complexity resulted in slow, expensive servicing and maintenance […] Two were apparently spotted derelict in the 1930s at Kars, by then in Turkey.”

There are no photographs of a fita class locomotive in the book. However this photo I spotted on display at the St Petersburg railway museum in March 2011 shows one:

The Russian-language Wikipedia has some basic information on the Ѳ class, though with no mention of Afghanistan. There is also a public domain image from the Kirov plant’s archive showing one with detail differences to the machine in the St Petersburg museum photo:

- Tenuous link to popular culture or what? And anyway, I thought the Moldovan gnomes should’ve won. ↩

Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World

This afternoon I was at the British Museum (along with what seemed to be half of London and a significant proportion of Europe) for the newly-opened exhibition Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World.

Enamelled glass goblet from Begram, 1st century AD (© Trustees of the British Museum)

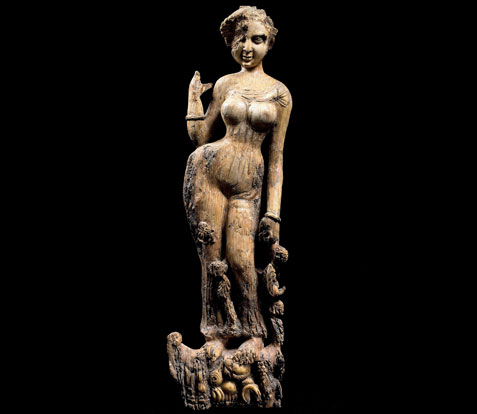

The exhibition offers an impressive display of shiny things from the National Museum of Afghanistan’s archaeological collections, ranging from Classical sculptures, polychrome ivory inlays originally attached to imported Indian furniture, enamelled Roman glass and polished stone tableware brought from Egypt, to delicate inlaid gold personal ornaments worn by the nomadic elite.

These showcase the trading and cultural connections of Afghanistan and how it benefited from being on an important crossroads of the ancient world.

The highlight for many visitors seemed to be a gold crown, though I was impressed by the enamelled glass (above).

All of these objects were found between 1937 and 1978 and were feared to have been lost following the Soviet invasion in 1979 and the civil war which followed, when the National Museum was rocketed and figural displays were later destroyed by the Taliban. Their survival is due to a handful of Afghan officials who deliberately concealed them and they are now exhibited here in a travelling exhibition designed to highlight to the international community the importance of the cultural heritage of Afghanistan and the remarkable achievements and trading connections of these past civilisations.

The earliest objects in the exhibition are part of a treasure found at the site of Tepe Fullol which dates to 2000 BC, representing the earliest gold objects found in Afghanistan and how already it was connected by trade with urban civilisations in ancient Iran and Iraq. The later finds come from three additional sites, all in northern Afghanistan, and dating between the 3rd century BC and 1st century AD. These are Ai Khanum, a Hellenistic Greek city on the Oxus river and on the modern border with Tajikistan; Begram, a capical of the local Kushan dynasty whose rule extended from Afghanistan into India; and Tillya Tepe, (“Hill of Gold”), the find spot of an elite nomadic cemetery.

Source: British Museum, November 2010

The exhibition was very busy on a Sunday afternoon, but I manged to get a ticket for timed admission within 40 min of arrival (you can pre-book online) and spent a bit over an hour inside. It isn’t heavy on detailed labels, just impressive exhibits. The exhibition is on from 3 March to 3 July 2011.

Some reviews

And the trains…?

At risk of stating the blindingly obvious, this exhibition of ancient artefacts contains nothing about railways. Having said that, flicking through the catalogue I found a description of the problems the Kabul museum has suffered. In 1995,

In the no-man’s-land behind the museum, one locomotive from King Amanullah’s railway stood rusting, the second one was stripped down for scrap metal.

Source: Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, Fredik Hiebert and Pierre Cambon (editors)

This again suggests that there was once two locomotives at the museum, which agrees with some other past news reports. Photos show three locomotives now, so where did the third one come from?

Indian ivory furniture support from Begram, 1st century AD (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Darulaman railway in 1926

This narrow gauge railroad ran from the Shah-do-Shamshira to Darulaman

; a photograph taken in 1926 at the Williams Afghan Media Project website. It is the same photo as the one from German magazine Uhu in February 1930, although Uhu cropped the edges.

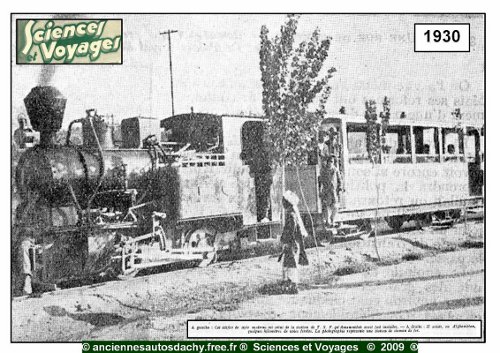

Kabul to Darulaman railway in 1930

“Train en afghanistan 1930” is a photograph of the Kabul to Darulaman railway, scanned from French magazine Sciences et Voyages No. 533 of 3 April 1930 by “Jean-Pierre 60”.

The original caption says Il existe, en Afghanistan, quelques kilomètres de voies ferrées. La photographie represente une station de chemin de fer

[There are, in Afghanistan, a few kilometres of railway. The photograph shows a railway station].

The locomotive has a headlight, which doesn’t appear on earlier pictures.

Steam loco at the National Museum of Afghanistan

The Museum And The Palace

at the From UBC to Kabul blog by Brian Platt has some photographs of the Kabul museum and its plinthed Henschel steam locomotive which were taken on 30 October 2010. One of the locos with a collapsed cab is also visible in one of the shots.

After wondering around inside for a while, I explored the outside yard of the museum. The most interesting piece was this, the rusted-out body of a steam engine. It’s from the 1920s when Amanullah, the leader of Afghanistan from 1919 to 1929, worked his ass off to modernize the country.

…

However, Amanullah’s policies were attacked viciously by various conservative factions in Afghanistan, and eventually he was forced into exile in Europe. All that’s left of his grand train visions are sitting on the lawn of the National Museum.

Source: From UBC to Kabul, 2010-11-03