This afternoon I was at the British Museum (along with what seemed to be half of London and a significant proportion of Europe) for the newly-opened exhibition Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World.

Enamelled glass goblet from Begram, 1st century AD (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The exhibition offers an impressive display of shiny things from the National Museum of Afghanistan’s archaeological collections, ranging from Classical sculptures, polychrome ivory inlays originally attached to imported Indian furniture, enamelled Roman glass and polished stone tableware brought from Egypt, to delicate inlaid gold personal ornaments worn by the nomadic elite.

These showcase the trading and cultural connections of Afghanistan and how it benefited from being on an important crossroads of the ancient world.

The highlight for many visitors seemed to be a gold crown, though I was impressed by the enamelled glass (above).

All of these objects were found between 1937 and 1978 and were feared to have been lost following the Soviet invasion in 1979 and the civil war which followed, when the National Museum was rocketed and figural displays were later destroyed by the Taliban. Their survival is due to a handful of Afghan officials who deliberately concealed them and they are now exhibited here in a travelling exhibition designed to highlight to the international community the importance of the cultural heritage of Afghanistan and the remarkable achievements and trading connections of these past civilisations.

The earliest objects in the exhibition are part of a treasure found at the site of Tepe Fullol which dates to 2000 BC, representing the earliest gold objects found in Afghanistan and how already it was connected by trade with urban civilisations in ancient Iran and Iraq. The later finds come from three additional sites, all in northern Afghanistan, and dating between the 3rd century BC and 1st century AD. These are Ai Khanum, a Hellenistic Greek city on the Oxus river and on the modern border with Tajikistan; Begram, a capical of the local Kushan dynasty whose rule extended from Afghanistan into India; and Tillya Tepe, (“Hill of Gold”), the find spot of an elite nomadic cemetery.

Source: British Museum, November 2010

The exhibition was very busy on a Sunday afternoon, but I manged to get a ticket for timed admission within 40 min of arrival (you can pre-book online) and spent a bit over an hour inside. It isn’t heavy on detailed labels, just impressive exhibits. The exhibition is on from 3 March to 3 July 2011.

Some reviews

BBC

Guardian

Independent

Londonist

Telegraph

And the trains…?

At risk of stating the blindingly obvious, this exhibition of ancient artefacts contains nothing about railways. Having said that, flicking through the catalogue I found a description of the problems the Kabul museum has suffered. In 1995,

In the no-man’s-land behind the museum, one locomotive from King Amanullah’s railway stood rusting, the second one was stripped down for scrap metal.

Source: Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, Fredik Hiebert and Pierre Cambon (editors)

This again suggests that there was once two locomotives at the museum, which agrees with some other past news reports. Photos show three locomotives now, so where did the third one come from?

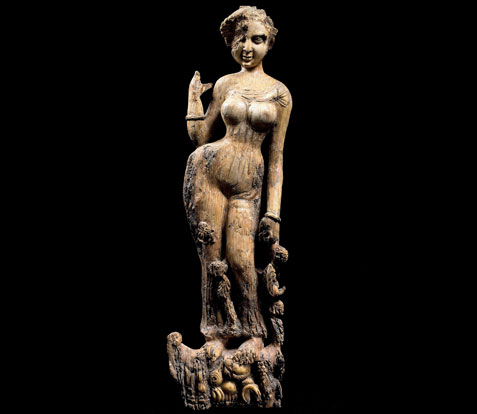

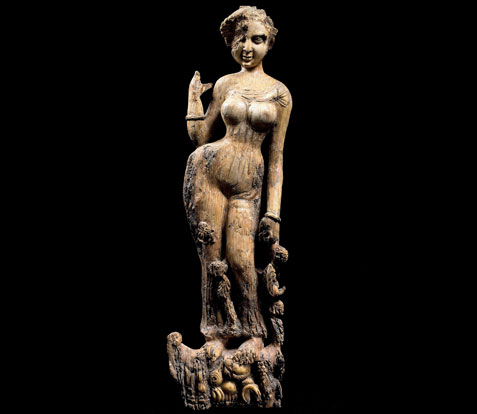

Indian ivory furniture support from Begram, 1st century AD (© Trustees of the British Museum)