Posted by Robert Grauman at Practical Machinist is an article about railway construction during the Great Game which appeared in 15 August 1885, issue of Scientific American, having originally appeared in French magazine L’Ilustration. I guess it is now out of copyright, so I’ll post it here too.

The Bolan pass is now in Pakistan.

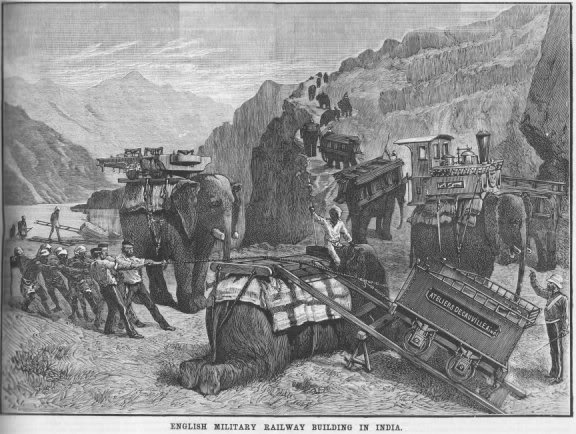

An English military railway

“The English army has succeeded in establishing a portable railway on several points of the Bolan Pass. This railroad is of the Decauville system, formed in sections of small steel rails, which can be put down or taken up very quickly. This ingenious railway – which has been used considerably for work on the Panama Canal and for the transportation of sugar cane in Australia and Java – has become the indispensable means of transport in all wars. It is at present being used in Tonquin and Madagascar by the French army, and is also being used on the Red Sea by the Italian army. When the Russian government commenced the war in Turkestan, in 1882, it bought one hundred versts, or about 66 miles, of the Decauville railroad, which Gen. Skobeleff used with great success for the transportation of potable water and for all the provisions for his army. This railroad was taken up as the army marched forward, and when the Russians advanced recently, in Afghanistan, the little railway appeared at the advance posts, and was described to the English army by the officers who watched the operations for the Afghans. An order for a similar apparatus was given by the English government to M. Decauville, directions being given that the road should be of the same type as that furnished to the Russians. The object of this was, probably, that any sections of road which might be captured from the Russians during the war could be used by the English. In this last order there was one problem which was very difficult to solve; all the material had to be carried by elephants, and they wanted a locomotive. M. Decauville had the locomotive made in two parts, the larger of which weighed on 3,978 pounds, the greatest weight that an elephant can carry.”“This episode of the Anglo-Russian conflict, illustrated in the annexed cut, is a great conquest for our national industry, for the works of M. Decauville are at Petit-Bourg, that is, in France, and only an hour from Paris. They cover about 20 acres on the bank of the Seine, and adjoin the P.L.M. The great hall is 525 feet long by 525 feet deep. The material is brought in at both ends (at one end the rails and steel for the road, and at the other end the sheet metal and iron for the cars), and the manufactured products are taken out at the middle, loaded in the cars of the P.L.M Co. In July, 1884, the works of Petit-Bourg attained their greatest development, with a thousand workmen, and 350 machines, which do the work of 3,000 men. Among others, there are four painting machines, which do the work of 60 painters. Three thousand cars and 93 miles of road are produced each month.”

Source: Scientific American, 15 August 1885, quoted at Practical Machinist‘s Antique Machinery and History forum 2010-02-26