An article at The Bug Pit, UN: NDN An Express Train For Afghan Drug Traffickers, draws attention to an October 2012 report from the UN Office on Drugs & Crime, Misuse of Licit Trade for Opiate Trafficking in Western and Central Asia: A Threat Assessment. This report contains information about rail transport in Central Asia, as well as lots of details of the movements of undesirable substances.

As Bug Pit author Joshua Kucera points out, “it stands to reason that making transportation easier would make illicit trafficking easier – especially in countries where border officials are notoriously corrupt.”

The UN report says:

Uzbek officials stationed at the [Hairatan] border are generally well trained and receive relatively high salaries. The risk of concealed drugs crossing the border undetected is therefore lower at the Hairatan BCP than it is in Naibabad.

(p65)

This issue has been raised at a couple of railway conferences I’ve been to in Turkey and the UAE, where it was suggested that providing decent jobs – particularly wages – for border officials in places like Central Asia can easily pay for itself in smoother regional trade, and also help to ensure that legitimate fees are charged and go where they should be going, rather than unofficial fees which disappear into black holes.

It was even suggested that dealing with these matters might offer better benefits for the cost than funding fancy new transport infrastructure.

The report also offers some information about trains:

The Hairatan [Border Control Point] primarily receives cargo arriving on the Termez-Hairatan railway from Uzbekistan. On average, 100-120 containers are sent to and from Hairatan BCP each day.26 Interview with Customs Officials at Dry Ports in Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif, March 2012. At the Hairatan BCP and Naibabad dry port, cargo is trans-shipped from trains onto trucks, which then travel along the assigned transit routes to Pakistan.

(p32)

and about boats:

The large river port at Termez ships approximately 1,000 tons of cargo daily to a location only 500 metres away from the Hairatan BCP in Afghanistan.

The road and railway link from Termez to Hairatan runs along the northern trade route and is part of

the Northern Distribution Network.137 The railway line was only completed in 2010. The railway line has the capacity to transport 4,000 tons of cargo per month and can cater for eight trains travelling in each direction per day. On average, 100-120 containers travel the route every day.138 US Department of State, http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/5380.htm Although the road leading from Hairatan to Mazar-e-Sharif has recently been improved, it is not capable of handling high levels of traffic. Therefore, cargo continues to be delivered to and from Afghanistan primarily along the railway route.

(p64)

The railway dates from 1982, and “4,000 tons of cargo per month” sounds rather low; perhaps that should be per day, meaning 500 tons on each of those eight trains – or 250 tonnes if both directions are included?

In 2007, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan signed a transport and transit agreement. […] Both countries also agreed to extend the Turkmen railroad network from Serkhetabad to Torghundi in the Afghan Herat province and to construct a trans-Afghan gas pipeline.

(p76)

The line is originally older than 2007, which was when Turkmenistan funded rebuilding and reopening it.

There are two main trade and transit trade routes leading from Afghanistan to Turkmenistan. The first is a direct road and railroad link from Torghundi in Afghanistan to Serkhetabad in Turkmenistan. On average, the rail services at Torghundi transport around 50 wagons per day, while Torghundi dry port trans-ships containers delivered by approximately 300-350 trucks per day. From Torghundi dry port, Afghan goods can be delivered via Turkmenistan to the Russian Federation or the Islamic Republic of Iran. From the Islamic Republic of Iran, they are shipped to countries in the Persian Gulf, or through Turkey to European markets.

(p77)

The report continues:

The second transit route is a railroad that runs from Afghanistan via Turkmenistan to the Islamic Republic of Iran. It begins at Mazar-e-Sharif in Afghanistan and terminates at the Iranian Bandar Abbas seaport:

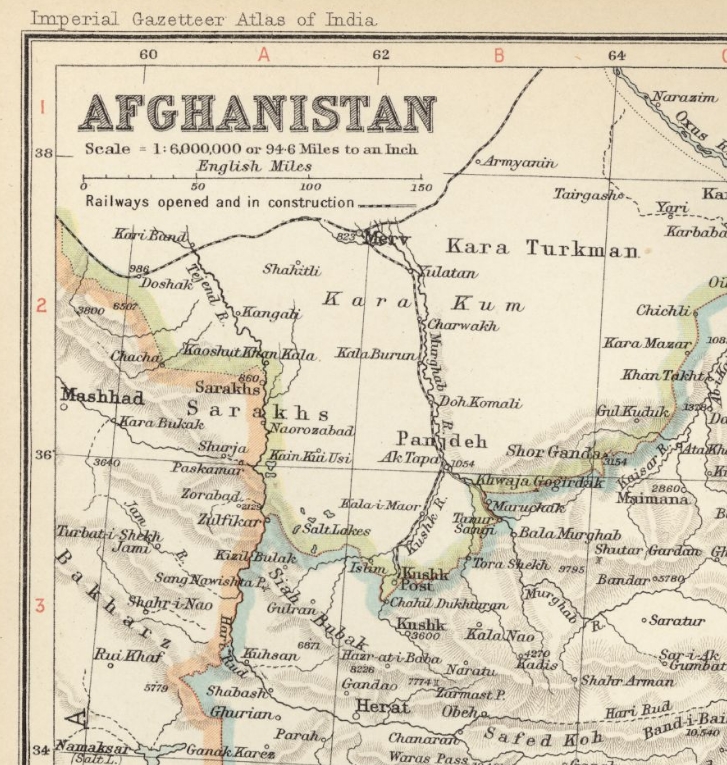

- Mazar-e-Sharif (Afghanistan) – Andkhoy – Chardzhou (Turkmenistan) – Serahs (Turkmenistan) – Mashhad (Islamic Republic of Iran) – Kerman – Bandar Abbas

(p77)

A Mazar-i-Sharif – Andkhoy – Turkmenstan railway is still only at the planning stage.

On a daily basis, approximately 50 vehicles cross the Imamnazar border in each direction180 Asian Development Bank, 2010, while a further 20-30 trucks cross at Serkhetabad.

(p78)