“Afghanistan’s first train … outside the Kabul Museum”. Photo on Flickr, taken by Charisse Louw and dated 10 November 2004 (© Charisse Louw, all rights reserved).

Darulaman

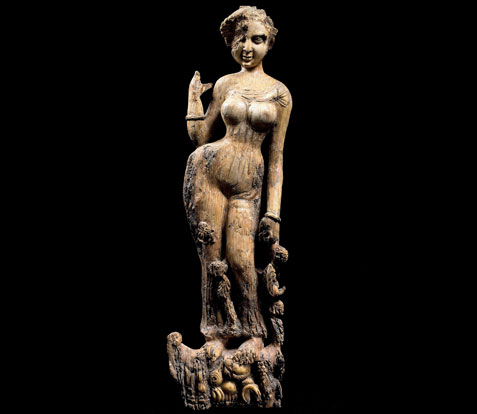

Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World

This afternoon I was at the British Museum (along with what seemed to be half of London and a significant proportion of Europe) for the newly-opened exhibition Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World.

Enamelled glass goblet from Begram, 1st century AD (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The exhibition offers an impressive display of shiny things from the National Museum of Afghanistan’s archaeological collections, ranging from Classical sculptures, polychrome ivory inlays originally attached to imported Indian furniture, enamelled Roman glass and polished stone tableware brought from Egypt, to delicate inlaid gold personal ornaments worn by the nomadic elite.

These showcase the trading and cultural connections of Afghanistan and how it benefited from being on an important crossroads of the ancient world.

The highlight for many visitors seemed to be a gold crown, though I was impressed by the enamelled glass (above).

All of these objects were found between 1937 and 1978 and were feared to have been lost following the Soviet invasion in 1979 and the civil war which followed, when the National Museum was rocketed and figural displays were later destroyed by the Taliban. Their survival is due to a handful of Afghan officials who deliberately concealed them and they are now exhibited here in a travelling exhibition designed to highlight to the international community the importance of the cultural heritage of Afghanistan and the remarkable achievements and trading connections of these past civilisations.

The earliest objects in the exhibition are part of a treasure found at the site of Tepe Fullol which dates to 2000 BC, representing the earliest gold objects found in Afghanistan and how already it was connected by trade with urban civilisations in ancient Iran and Iraq. The later finds come from three additional sites, all in northern Afghanistan, and dating between the 3rd century BC and 1st century AD. These are Ai Khanum, a Hellenistic Greek city on the Oxus river and on the modern border with Tajikistan; Begram, a capical of the local Kushan dynasty whose rule extended from Afghanistan into India; and Tillya Tepe, (“Hill of Gold”), the find spot of an elite nomadic cemetery.

Source: British Museum, November 2010

The exhibition was very busy on a Sunday afternoon, but I manged to get a ticket for timed admission within 40 min of arrival (you can pre-book online) and spent a bit over an hour inside. It isn’t heavy on detailed labels, just impressive exhibits. The exhibition is on from 3 March to 3 July 2011.

Some reviews

And the trains…?

At risk of stating the blindingly obvious, this exhibition of ancient artefacts contains nothing about railways. Having said that, flicking through the catalogue I found a description of the problems the Kabul museum has suffered. In 1995,

In the no-man’s-land behind the museum, one locomotive from King Amanullah’s railway stood rusting, the second one was stripped down for scrap metal.

Source: Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, Fredik Hiebert and Pierre Cambon (editors)

This again suggests that there was once two locomotives at the museum, which agrees with some other past news reports. Photos show three locomotives now, so where did the third one come from?

Indian ivory furniture support from Begram, 1st century AD (© Trustees of the British Museum)

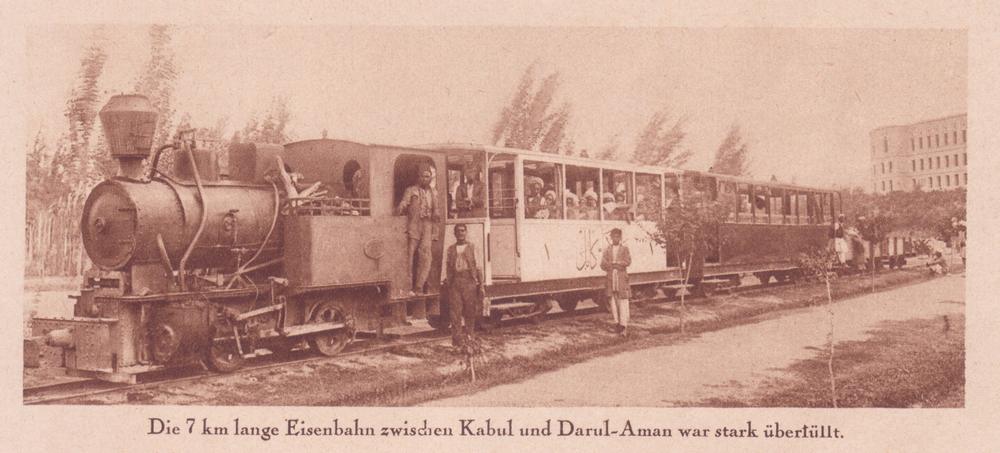

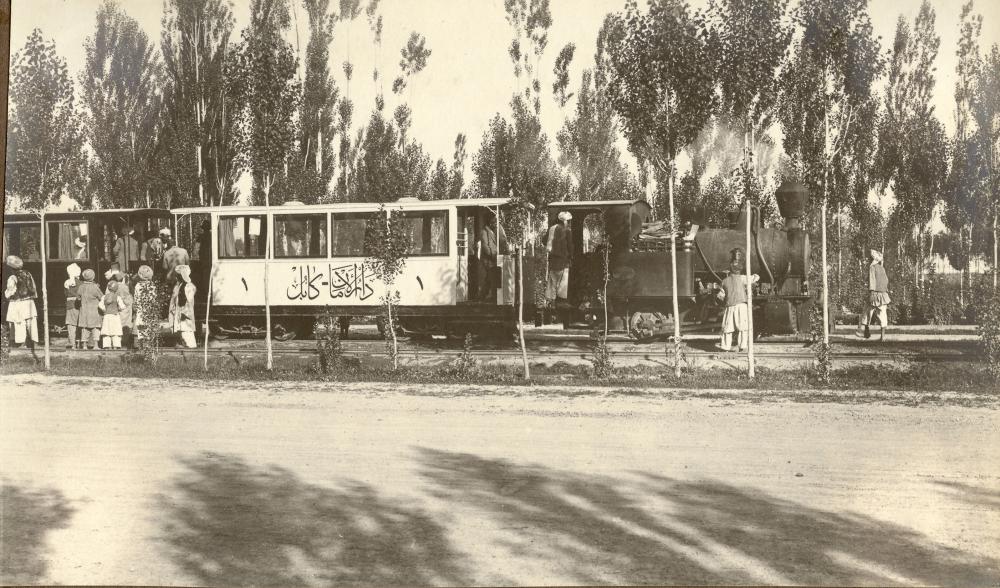

Darulaman railway in 1926

This narrow gauge railroad ran from the Shah-do-Shamshira to Darulaman

; a photograph taken in 1926 at the Williams Afghan Media Project website. It is the same photo as the one from German magazine Uhu in February 1930, although Uhu cropped the edges.

Accident on the Darulaman railway

Telegrams in Brief.

The only railway in Afghanistan, the narrow-gauge line between Kabul and Dar ul Aman, the new city built two years ago by King Amanullah, had its first serious accident last week, when an engine overturned, killing one man and injuring two. Its driver, a Peshawari Pathan, escaped.

The Times, 19 June 1928, p15 (Issue 44923, col G)

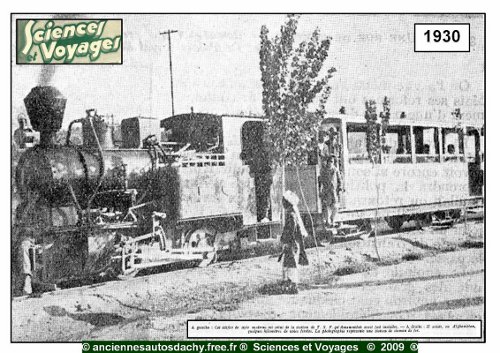

Kabul to Darulaman railway in 1930

“Train en afghanistan 1930” is a photograph of the Kabul to Darulaman railway, scanned from French magazine Sciences et Voyages No. 533 of 3 April 1930 by “Jean-Pierre 60”.

The original caption says Il existe, en Afghanistan, quelques kilomètres de voies ferrées. La photographie represente une station de chemin de fer

[There are, in Afghanistan, a few kilometres of railway. The photograph shows a railway station].

The locomotive has a headlight, which doesn’t appear on earlier pictures.

Steam loco at the National Museum of Afghanistan

The Museum And The Palace

at the From UBC to Kabul blog by Brian Platt has some photographs of the Kabul museum and its plinthed Henschel steam locomotive which were taken on 30 October 2010. One of the locos with a collapsed cab is also visible in one of the shots.

After wondering around inside for a while, I explored the outside yard of the museum. The most interesting piece was this, the rusted-out body of a steam engine. It’s from the 1920s when Amanullah, the leader of Afghanistan from 1919 to 1929, worked his ass off to modernize the country.

…

However, Amanullah’s policies were attacked viciously by various conservative factions in Afghanistan, and eventually he was forced into exile in Europe. All that’s left of his grand train visions are sitting on the lawn of the National Museum.

Source: From UBC to Kabul, 2010-11-03

CNN on Afghan railway projects

After nearly a century, a modern Afghan railroad is under construction, reports CNN. “This connects Afghanistan to the world,” says an 18-year-old high school student named Shakrullah. He says he hopes to one day get a job as an engineer for the railroad. “I want trains for all the provinces of Afghanistan, not just for Balkh province.”

Italian engineers and electrification plan

FIRST AFGHAN RAILWAY

(from our own correspondent)

SIMLA, Sept.20.Italian engineers in Kabul are reported to be collecting engines and rolling stock for the first railway to be opened in Afghanistan between Kabul and Darulaman, six miles from the capital. The construction of the line is expected to begin shortly. The possibility of making it an electric tramway is discussed in certain Afghan papers.

The Times, 30 September 1922, p9 (Issue 43150; col G)

The reference to Italian engineers is interesting – one might have expected the people involved to be German.

Kabul railway parcel stamp

The Trains on Railway Parcel Stamps & Railway Letter Stamps of the World pages of the Aphabetilately website includes a picture of a 1923 issue of a 2 paisa railway parcel stamp from the railway to Darulaman. A paisa was a subbdivison of the Afghan rupee used in the 1920s.

The stamp is described as “small quantity issued, no used copies seen”, citing page 29 of Patterson, presumably Afghanistan: Its Twentieth Century Postal Issues by Frank E Patterson III (New York; The Collectors Club, 1964).

The logo is the national emblem of Afghanistan, first used during the reign of King Amanullah and now in the centre of the current national flag. It shows a mosque, with the mihrab (the niche indicating the direction of Mecca) and a minbar (pulpit), with a royal shako (hat) above. The rays forming eight points were inspired by the 19th century Ottoman Imperial standards, and the shape changed from a circle to an oval in 1921, according to the Afghanistan 1919-1928 section of the Flags Of The World website.

Kabul railway coach photo

Google’s archive of photos from Life has this one (above) captioned “Deserted Afghan railway car after failure to begin rail system”.

Dated 1938 in the caption, the picture shows an overgrown bogie coach from the short-lived narrow gauge railway which ran for 7 km between Kabul and Darulaman.

The number painted at each end is “2” – a vehicle number, or a class number? The coach is noticeably longer than one in labeled “1” in this picture below, which was taken by Wilhelm Rieck in 1923 and is said to show the first train, so perhaps it is a class number, with the bigger coach being second class.

The Life photo shows another coach at the back, apparently a lighter colour, which is presumably the first class car. But is there a third vehicle as well, in front of that one?

This picture below appeared in the February 1930 issue of the German magazine UHU, and shows two coaches plus some wagons.

Amazingly, the locomotives have survived, though only the underframes of the coaches remain.